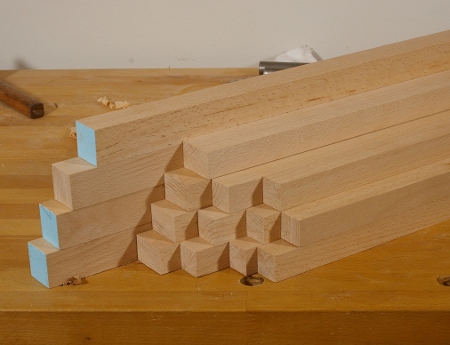

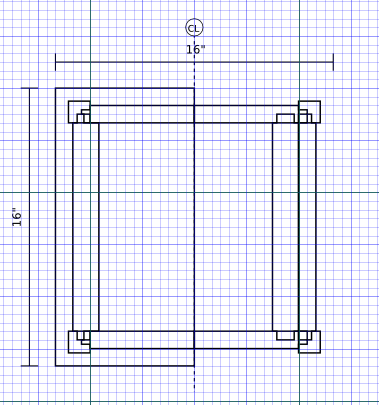

With the panels milled to thickness, it was time to make the grooves in the frame to house them. Normally, this isn’t such terrible work; I don’t have a plow plane, but I do have a router plane with a fence that I made and it works, just not as quickly as a plow. With this project, however, there were a few additional matters:

- I needed an additional fence setting, because the grooves in the legs go at a different offset than the stretchers.

- There are more than three times as many grooves to make in this project than my previous project.

- All of the leg grooves are stopped on both sides.

- Two of the stretchers have strange profiles.

- Beech is much more difficult to work than the stuff I’ve used for other projects with panels.

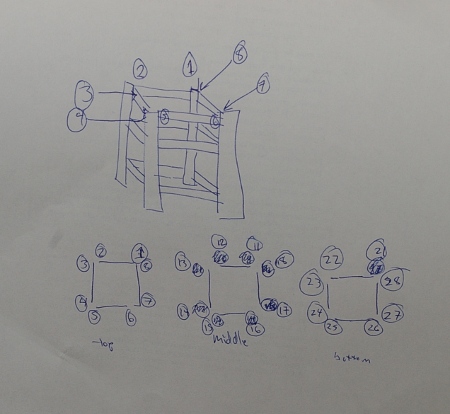

I started by modifying my homemade router plane fence. First, I took it apart and replaced the wood screw fasteners with screw inserts and brass machine screws so that it would be easier to move around:

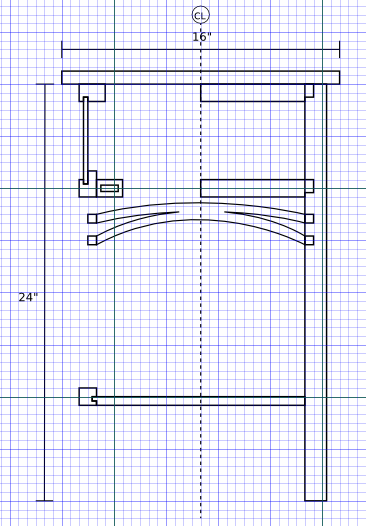

Then I drilled a few more holes at different offsets on the fence mount so that I could move the fence sideways. Here’s a view of the complete router plane and fence:

With this done, I did the grooves for the stretchers. These were mostly straightforward, except for the ones on the side middle. Viewed from one end, these have J-shaped profiles because they form part of the enclosure for the drawer. (I don’t think I will ever design anything like this again; I’ll just use additional stretchers or something to avoid complications like this.)

So first, I had to cut a groove about 3/4″ deep into the stretcher:

Then I scribed a line from the bottom of this to the proper height and sawed off most of the waste. The first time, I did it freehand (as shown below), but on the second one, I wised up and clamped a batten on top to use as a sort of guide.

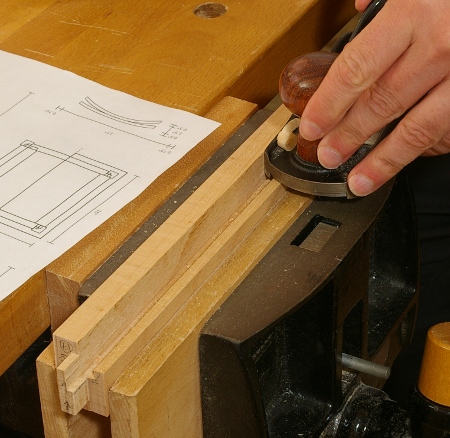

Finally, I used a block plane to bring the side down to final height:

The stretchers were then out of the way, but the grooves in the legs remained, so I moved the fence on the router plane and did them.

The whole process took quite a long time. A plow plane would have made very quick work of the stretchers because those grooves aren’t stopped. However, the leg grooves were just slow going. There’s just a lot of constant time-consuming adjustment when you go progressively deeper on a router plane, especially an older one like this, where there is a little bit of play in the blade alignment. You have to be a little careful about how you tighten it. I imagine that the Veritas router plane doesn’t have this problem, but I’m not shelling out the dough to get one of those when I’ve already got one that works (I’d rather have a plow plane).

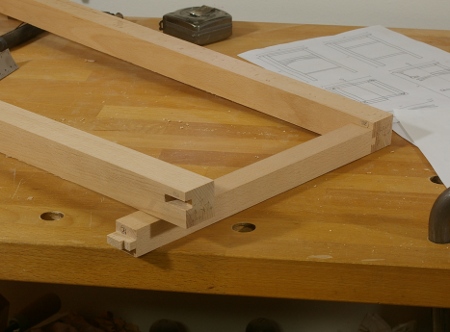

At long last, I was ready to start sawing the panels to size and fit into the grooves this morning. Turned out well; I now have the sides done (the back requires a glueup which is in progress):

I’m almost ready to glue up some of the frame.