With the tool storage in a somewhat usable state in the new shop, I finally had a chance to restart the tool cabinet project last week. I finished the carcase before the move, so I’m left with the doors and some other odds and ends. I decided to start with the rear, which will have two cross-members to aid with mounting on the wall and internal tool arrangement.

After taking what seemed to be an eternity to size up the pieces, I made the first joint for the members in the back. Then I realized that it was the first joint that I’d made in the new shop, so I took a photo to commemorate the occasion:

That’s the wacky Taiwan-made chisel featured in this post, chosen this time by the ever-reliable “I was actually able to find that one” method. Though this joint was perfect in the end, I can’t say that it went without a hitch–for some reason, when marking out the tenon, I had set my mortise gauge incorrectly and just barely noticed in time. Unlike the saw till, I’ve decided not to use wedged or through joints here.

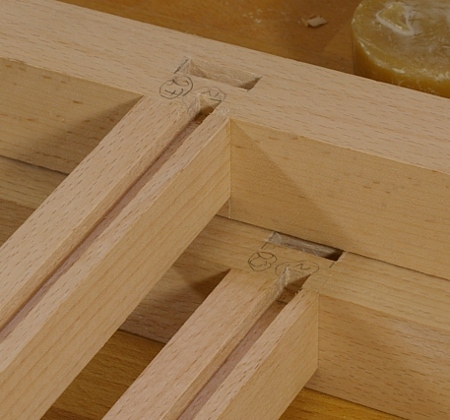

Okay, so that wasn’t terribly exciting, nor was it difficult. Soon it was time for the cabinet door frames. I made up my mind to use the mitered-face mortise-and-tenon joint for this application. The main reason is that I really would like some practice at this thing, and I’d much rather screw it up on a shop project than something I actually care about. Nevertheless, it seems to be going well so far:

The pile of components for this project is much larger than I anticipated:

I already had to go out to get more wood for it twice. Normally, this would be an incredible miscalculation, but since I can’t say that I’ve actually bothered to calculate, there’s probably another word or two for it that isn’t nearly as nice.

The shop seems to be usable. The intermediate state of the tool wall looks like this now:

The thing at the center top is a sort of shallow shelf-like thing that I made for the french cleats. The scrub plane just happens to fit on top, so I put it there because it seemed like a good idea at the time. The chisel rack is a reincarnation of the lamest tool rack ever built; for some reason, I brought it intact from the old place, and added cleats and screwed stuff into it until it actually fit on the wall. The space to the right is where the tool cabinet will eventually go.

And really, the cabinet can’t come too soon. This is what I’m dealing with on the benchtop right now:

Mind you, this was after cleaning up a bunch of stuff. There are tools in all sorts of weird places around the place and I keep getting nervous that I’m going to knock them over–I don’t have a lot of room to move around.

Oh yeah–thanks to Jasen, who lent me that Narex 3/16″ mortise chisel. For that size, I don’t have any of my own (yet).

[Edit: I didn’t notice at the time, but this is post #200.]