I’m slowly making my way through the prototype bookshelf project. After realizing that my widths were all wrong, I had to spend some quality time with my rip saws and jointer plane to fix all of it, and I was able to do that during what little time I had this weekend.

So then I decided to get started on the dovetail joints for the top, and let’s just say that my dovetails are not the famous five-minute variety. I don’t get a lot of uninterrupted time in the shop these days, so I just cut whatever I can, and stop when I need to. On Monday, I laid out the tails and cut them. Yesterday, I only had time to finish cleaning the waste between the tails and mark out the pins. This morning, I had enough time to cut the pins and finish the joint (and mark out the tails for the next joint). So it may not be the 60-year dovetail, but sometimes it seems like that.

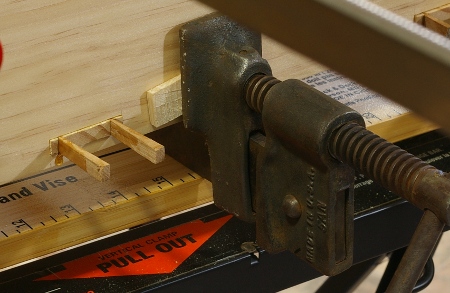

However, the story is not a sad one. For one, the joint is perfect; the only thing left to do here is plane off the proud excess at the ends of the tails and pins:

Another bright spot is that it went off without a hitch, even on pain-in-the-butt yellow-poplar sapwood (the lighter bits on the right). Saw, chop, and test-fit. The pins fit right off the saw; no paring was required on the sides of the pins. Thinking back to the first dovetail joints I made, it took much longer to cut joints that did not turn out as well. My speed is improving.

I’m back to using my cheap Crown gent’s saw, still with the same touching up of the teeth that I gave it when I first got it (slight jointing, filing with a needle file, slight stoning on the sides to remove some of the set, and wax). It works fine, though I can’t imagine how bad it would have been if I hadn’t tuned it. I am still plotting out the dream dovetail saw that I will make one day, but I’m too busy with furniture projects right now to get tied up with making another stupid tool, and honestly, it’s just not that important.

Sometimes I think of what could possibly make things move a little faster, and I came to the conclusion that some operations are actually going quickly but some not so quickly.

The fast ones are:

- Sawing down the tails and pins

- Removing the bulk of the waste

- Test-fitting

The stuff that seems to take a little longer:

- Laying out the joints

- Paring down the final little bits in the tail and pin troughs

Now, I know that the paring could go a little quicker if I just bothered to make a pair of skew chisels. I really should get on that case some day.

What about laying out the joints, though? I do this mostly by eye now, marking out “what looks good” (to me, at least) for the tail spacing, then using a square and T-bevel to mark the lines. This works and it is St. Roy- (and others) approved. But it’s not fast for me. I can mark the spacing quickly enough, but lining up the T-bevel to the mark on top always seems to take a little extra time. A dovetail template could save some time, because you can register it to your marks at the top quickly.

But then again, we’re talking about a savings of only about two or three minutes here. And I don’t think it’s worth getting yet another tool for that at the moment. Furthermore, I can’t just arbitrarily pick the angle I want, as I do now. I know that’s been said a million times before, but I do think it counts for something.