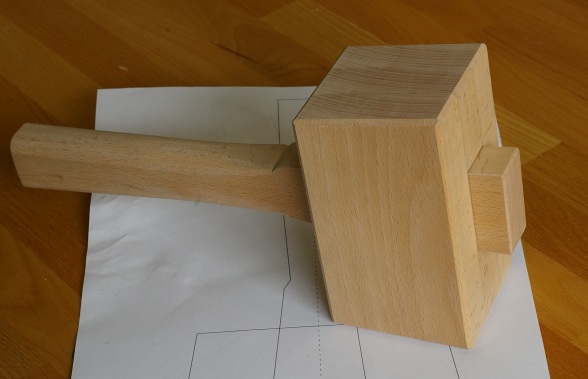

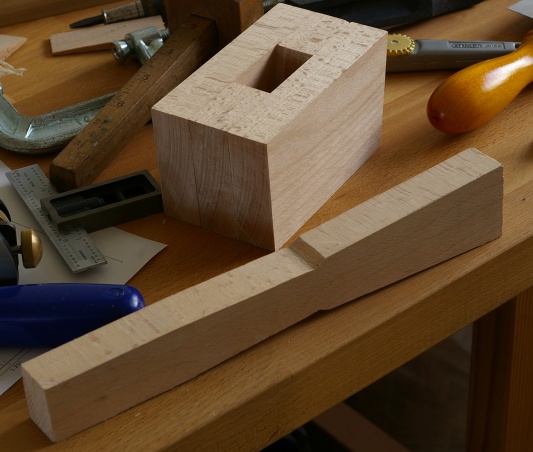

I decided to attack the long, wide groove to fit the tote today. I wasn’t too sure how to approach this, so I decided to see if a router plane would do what I needed it to. Having never used this tool (a Millers Falls #67 with a Lee Valley blade), I sharpened the blade and tested it on a piece of Douglas fir that usually sees test victim service. It seemed to work, so I set out clamping the plane body to the bench, marked the sides, and sawed down as much as I could:

Then I attacked it with the router plane until I got to the bottom. I had to remove the last part by chisel. (Next time, I will try to design the tote so that I can do the whole thing with the router plane. This was a severe pain in the butt.)

Finally, I shaved the edges of the groove so that the tote would fit snugly:

This could have turned out a little better, I guess. I was a little paranoid about trusting my lines when I sawed down, and it turns out that I shouldn’t have–they were dead on. In the end, there’s sort of a small gap on one side of the groove between the tote and the body. All in all, though, this went a lot better than the complete disaster that I expected…